May 2nd 1962, a balmy night in Amsterdam; the night of the long shots. Real Madrid race into a 2-0 lead through Ferenc Puskas’ cannonball drives, but within ten minutes Benfica draw level. Within an hour of kick-off, it’s 3-3; an average of goal every ten minutes. This is the 7th European Cup final, pitting the old masters from Madrid, winners of the first five tournaments, against reigning champions Benfica. Even in their mid-thirties Alfredo Di Stefano and Ferenc Puskas are not willing to go quietly into the night, they will not pass the torch to their youthful opponents. If Bela Guttman’s men want it, then they must be strong enough to wrest it from the grip of arguably the greatest club side in football history.

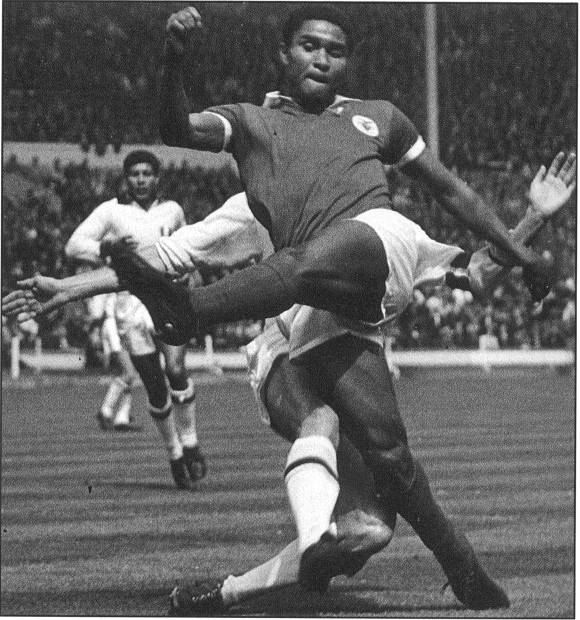

They are strong enough. None more so than their 20 year old revelation from Mozambique, Eusebio. With the scores level, the man (or perhaps, at this stage, the boy) who would go on to be known as ‘the Black Panther’ outpaces his hero, Di Stefano and is brought down inside the box. As he prepares to take the resulting penalty, Araquistan, the Madrid goalkeeper, roars insults at him in Spanish: faggot, little negro, bitch. A confused Eusebio turns to Mario Coluna for translation. “Just shoot,” his teammate tells him. “And I’ll tell you later.” And shoot he did. Five minutes later, he sent the ball flying past Araquistan once again, a 25 yard thunderbolt that put Benfica 5-3 up. The Cup was won, the torch was passed, but Eusebio had other matters on his mind. When the final whistle blew, he sprinted 30 yards for the chance to swap shirts with Puskas. Visibly awe-struck by this brush with one of his heroes, it’s difficult not to speculate whether he even knew what was happening as ecstatic Benfica supporters carried him from the pitch. Later Araquistan would approach him to apologise, and later still, L’equipe magazine would judge him the 2nd best player in Europe. It was his first full season as a professional.

Eusebio would go on to three more European Cup finals and his 9 goals at the 1966 World Cup would not only help Portugal to a 3rd place finish (their best ever), but also win him the tournament’s Golden Boot. He would win the Ballon d’Or in 1965 and, would finish within the award’s Top 5 for 5 consecutive years; a record only bested by Franz Beckenbauer and Lionel Messi. He scored 733 goals in 745 matches, including 41 international goals in just 64 caps for Portugal; a tally that has taken Cristiano Ronaldo over 100 games to better.

But in that glorious May night in Amsterdam lies the perfect illustration of why this railroad worker’s son from Lorenco Marques was so beloved across the footballing world that the government of Portugal declared 3 days of national mourning upon his death. In his two goals, we have the steely determination and irresistible skill that would enrapture crowds across Europe for over a decade. In his handling of Araquistan’s aggressive gamesmanship, there’s an enticing combination of childlike innocence and unselfconscious nobility. And in his desperate, joyful dash to exchange shirts with his idol, the gap between the stars that shine in the sport’s firmament and the fans that are dazzled by them, is briefly, and beautifully, bridged.

2 years after that final, Mozambique would declare independence from Portugal and war ensued between the two nations. Having been officially declared ‘a national treasure’ by Portuguese dictator Salazar, Eusebio would continue to score goals in the colours of his adopted country and their capital. But his efforts for Portugal did not extend beyond the football pitch, he later insisted that had he been asked to enlist in the army he would have fled rather than kill his countrymen in Mozambique. This assertion – and the efforts of his own brother who fought in Mozambique’s resistance – cut little ice with rebel leader, and later president, Samora Machel, who declared the Black Panther a traitor. For 9 years the greatest footballer to ever emerge from Africa was forbidden to return home – even for his own mother’s funeral.

Traitor is a dirty word, but there are no doubt some who wish Eusebio had taken a greater stand against Portuguese fascism and colonialism. The moral responsibility of high profile sportsmen is a deeply complex issue, but debating about it here is to opt for the abstract over the apparent (which is, admittedly, not always a bad choice, but how and ever): Eusebio was no Cruyff or Kopa, well-versed and outspoken on social issues. He was not even a Maradona, who tried to compensate in passion for what he lacked in nuance. Eusebio was a pure footballer, innocent to the point of naivety and passionate to the point of myopia. Eusebio was the childhood joy of playing the game combined with the adult mastery of the sport. He represented football’s simplest pleasures on its grandest stage. “There is no real substitute for a ball hit squarely and firmly” sang Billy Bragg. To see Eusebio dashing with almost aimless ecstasy, arm aloft and tongue out, having scored yet another goal, was to know the truth of this.

Leave a comment